Value Chain Analysis

Value chain analysis is about mapping the roles and responsibilities of different actors to identify threats and opportunities. The aim is to create strategies that enhance and help monitor the supply chain to inform the public and private sectors (Charry, et al. 2017). At its core, a value chain analysis is a description of the pathway which extends on one end from pre-farm input providers all the way to consumers linking industry stakeholders. This document highlights the need of building capacity across all CSA objectives, this requires careful monitoring and evaluation of supply chains. Results of these analyses facilitate the scaling up of CSC projects and the engagement of stakeholders in the execution and follow-up stages.

Mapping the value chain

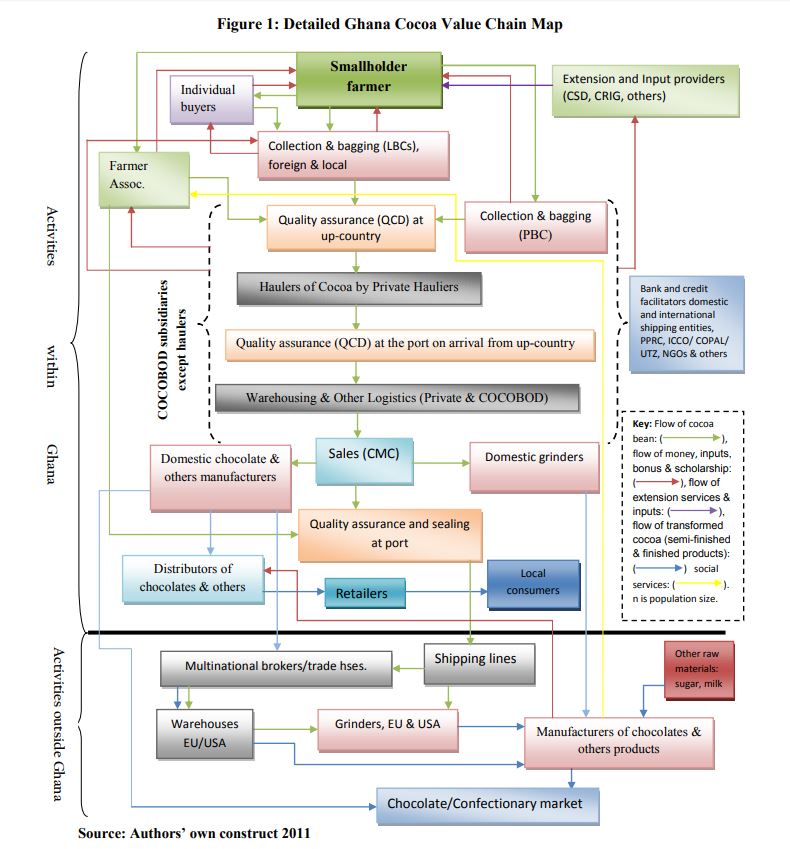

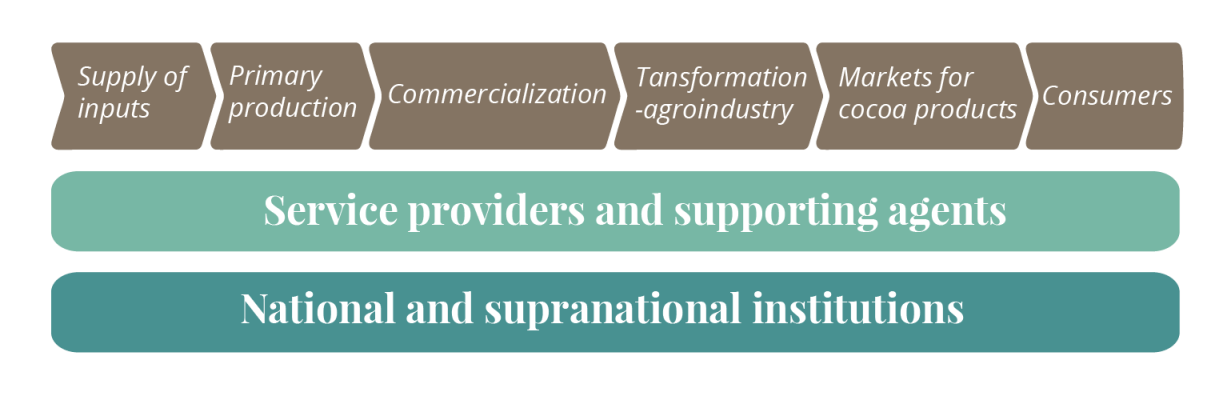

A value chain map is a graphical representation of the value chain that showcases the functions of stakeholders, their relationships and the agents supporting the process. Value chain maps are a key instrument in value chain analysis. A value chain can be structured on three levels: the first level includes stakeholders directly involved in the process of production, commercialization and consumption; at the second level are service provides and supporting agents; finally, at the third level are actors are national and supranational institutions lending support or laying the institutional groundwork (Charry, et al. 2018).

Quantification and description of the value chain

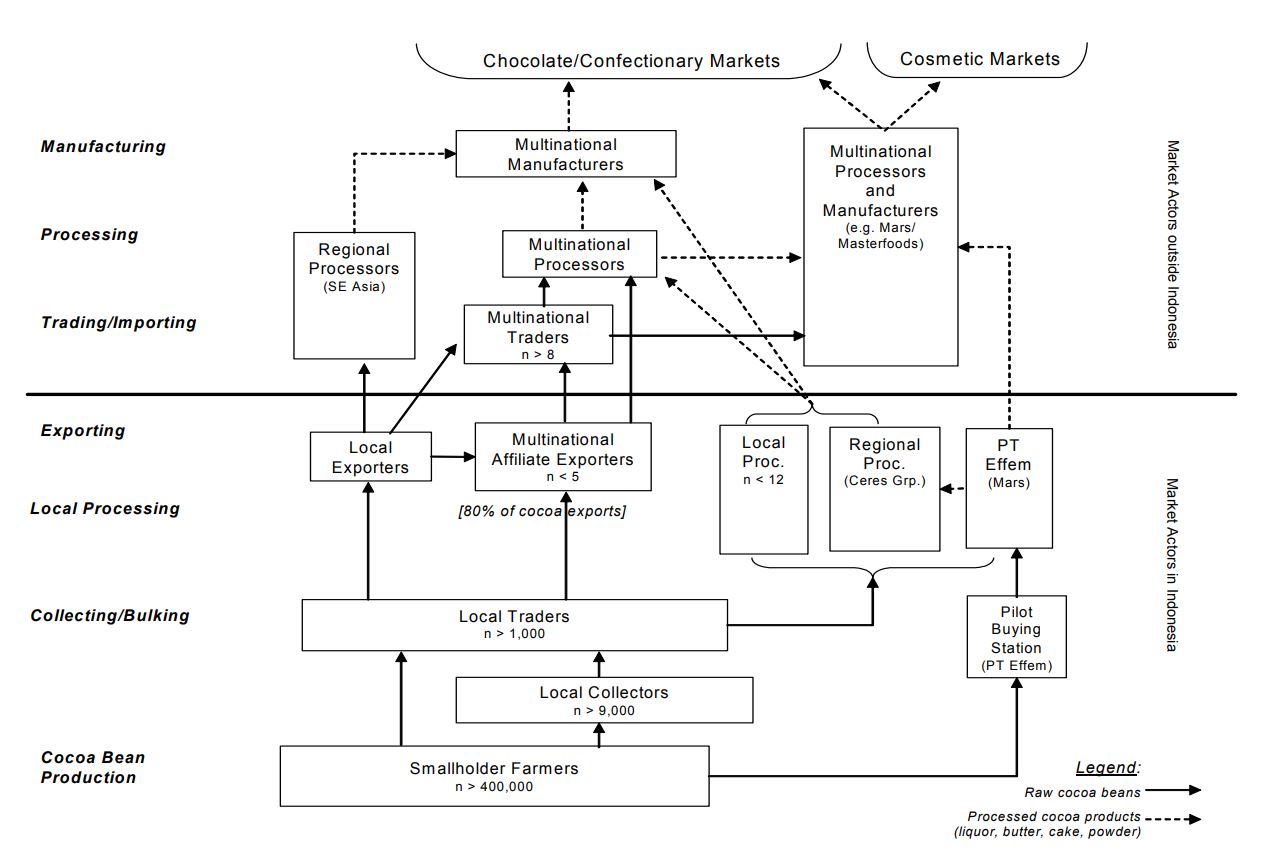

Quantification of the value chain adds a layer of depth to value chain maps. At this stage, information on the number of actors at each link of the chain as well as the volume of production they deal with and how the market becomes segmented is presented. The functions of relevant stakeholders are described as well as their interactions with each other at each of the levels noted above. Pre-farm actors provide inputs and services to farmers for their production. This includes seedling providers (e.g. seedling gardens), sellers of agrochemical inputs, etc. (Charry, et al. 2018). Farmers are at the primary production stage of cocoa-based supply chains. There are over 5 million cocoa smallholders in the world with 1.5 million in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana alone (Bunn, et al. 2018). The area planted by farmers varies; cocoa farms in Ghana are 2.6 hectares on average, while in Colombia it is 1.7 ha (Charry, et al. 2018). The amount of cocoa harvested, and its price partially determine farmer incomes. For cocoa farmers in Côte d’Ivoire profits from cocoa constitute 72% of their income (Fairtrade, 2018). Farmer groups are also included at this stage of the value chain, the number groups and participation rates of farmers is useful information for the trial and scaling up of projects.

Farmers can be categorized based on the degree of technification and diversification of production (Benjamin, et al. 2017). Differences between these categories are found in their farm management practices including input use and investment into production technologies. Farms are also often classified according to the percentage of shade cover, whether they are certified, and whether their production methods are traditional or there is a high degree of technification.

The link that follows primary production is commercialization, which can include individual purchasers, producer associations, and the purchasing agents of large firms (Charry, et al. 2018). Agents involved at this stage of the value chain act based on world market prices for cocoa as traded in the London and New York stock exchange. Governments, international institutions, and commercialization agents can be involved in technical assistance and distribution of inputs. Moreover, there are significant differences between the value chains of different countries regarding the degree of market liberalization, ranging from the liberalism of the Indonesian cocoa bean export market to the price adjustments and government-sponsored quality control division of Ghana’s COCOBOD. Finally, cocoa moves along the supply chain from commercialization agents to firms involved in transformation of cocoa and production of cocoa-based products such as chocolate bars, beverages, and cosmetics. The value added at each step of the value chain is unequally distributed. Benefits form price increases tend to benefit the agroindustry more than farmers.

Economic analysis

After mapping the value chain and quantifying and describing its links, economic analysis can reveal points of economic inefficiency, i.e., where resources are not used in an optimal way and minimizing waste. Furthermore, the economic analysis involves identifying where value is aggregated along the value than and where the transaction costs of research and negotiation lie. Benchmarking, which refers to taking stock of the principal parameters of a value chain, is a tool within economic analysis that facilitates the comparison between similar or related value chains. The economic analysis starts out at the evaluation of farmer costs of production. The categorization of cocoa farms according to their degree of technification and diversification is related to their balance sheets, although farmers very rarely record their costs and benefits of production.

Scaling of CSC projects

Value chain analysis is useful for scaling up projects and involving stakeholders at multiple levels. CSA combines is based on three pillars that coincide with the objectives of multiple actors along the value chain, therefore stakeholders should foster a sustainable CSC-based intensification pathway for the development of sustainable intensification of cocoa farms. However, as Bunn, et al. (2017) point out, “no single technology or scaling pathway may account for the diversity of decision environments of the actors involved”. The authors suggest, instead, a platform approach which involves the development of no-regret approaches to the adoption of CSC practices such that public and private actors can collaborate and engage with CSC recommendations based on their own preferences and available information.

Lundy (2018)

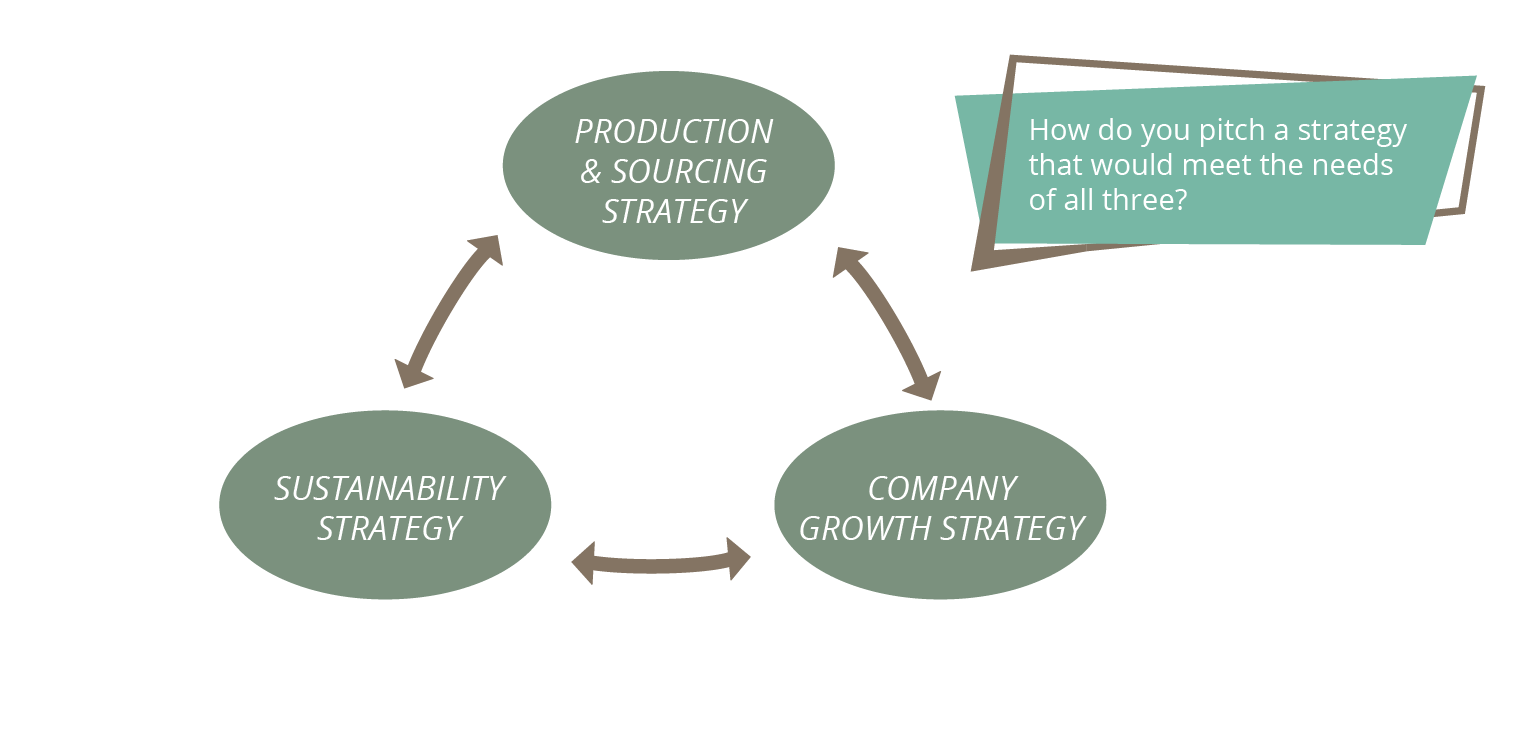

For companies involved in the cocoa value chain, aligning Corporate Social Responsibility and value chain related investments has the capacity to increase the effectiveness of their programs. Climate related objectives and initiatives can be aligned with the overall sustainability, production, sourcing, and growth strategy of the firm. CSC initiatives can comprehensively address the supply chain challenges related to short term volatility and long-term security of supply. Loss of suitable areas for cocoa production will increase the difficulty of sourcing cocoa.

Contribution to CSC

Value chain analysis can provide insights into the incentive structures of stakeholders in terms of the achievement of CSC objectives. The objectives of large and small stakeholders often coincide, but they are encumbered by the structure of the value chain.

Productivity: Actors at the manufacturing and processing stages prefer a consistent and secure supply of high-quality cocoa beans, this does not always translate, however, into higher price premiums for farmers whose management practices lead to these results. Improving the identification of farmers who adopt practices that lead to CSC objectives can improve the creation of price premiums and incentive structures.

Adaptation: Adaptation is linked to productivity in the value chain. As productivity linkages are created and reinforced, farmer incomes increase and so does their financial and investment capacity. Moreover, better value chain links with institutions and private business improve farmer access to extension services, information, and inputs for plot adaptation and landscape level resiliency improvements. The LINK methodology (Lundy, 2014) can be a successful approach for increasing value chain inclusivity and the pursuit of environmental objectives.

Mitigation: Large firms are often searching for ways to reduce the emissions of GHGs of their supply chain. In cocoa agroindustry firms this objective can be promoted at the primary production stage by promoting CSC practices that contribute to mitigation.